Past Projects

A selection of my past work and projects, from 2016-2019.

Biographical Prototypes: Reimagining Recognition and Disability in Design

In the design profession, stories involving disability often cast people with disabilities as non-designers and designers as saviors, or the creators of technologies that benefit people with disabilities. However, people with disabilities have always meaningfully contributed to the design profession. As a partial response, Burren Peil, Daniela Rosner, and I introduced biographical prototypes, under-recognized first-person accounts of design by people with disabilities. To guide their development, we drew on counter-storytelling from disability activism and critical race theory.

During workshops with disabled activists, designers, and researchers, biographical prototypes engendered an expanded sense of coalition among attendees while prompting reflection on tensions between recognition of design work and exhaustion and disinterest in becoming tied to design and research professions that have neglected accessibility for so long. We end by reflecting on how the prototypes—and the practices that produced them—complement a growing number of design activities around disability that reveal complexities around structural forms of discrimination and the generative role that personal accounts may play in their revision.

Diana loves to craft. After spilling beads one day, she wasn’t sure how she would collect them since she has difficulty reaching far from her chair. This biographical prototype represents her story adapting a spatula to ease bead pickup. She wrapped it in double sided tape so the beads would stick and the spatula’s handle elongated her reach so she could sweep it around the floor.

Thinking of trying the activity? Please feel free to be in touch with questions or your experiences creating and sharing biographical prototypes among people with disabilities, designers, researchers, and the public.

The Promise of Empathy: Design, Disability, and Knowing the “Other”

In this 2019 CHI paper, Daniela Rosner and I critically examined empathy-building which has become an important precursor to good design in user experience and Human-Computer Interaction fields. Promising to foster understanding, activities spanning observation to the simulation of bodily impairments aim to help designers imagine what it might be like to be someone else, often their intended users.

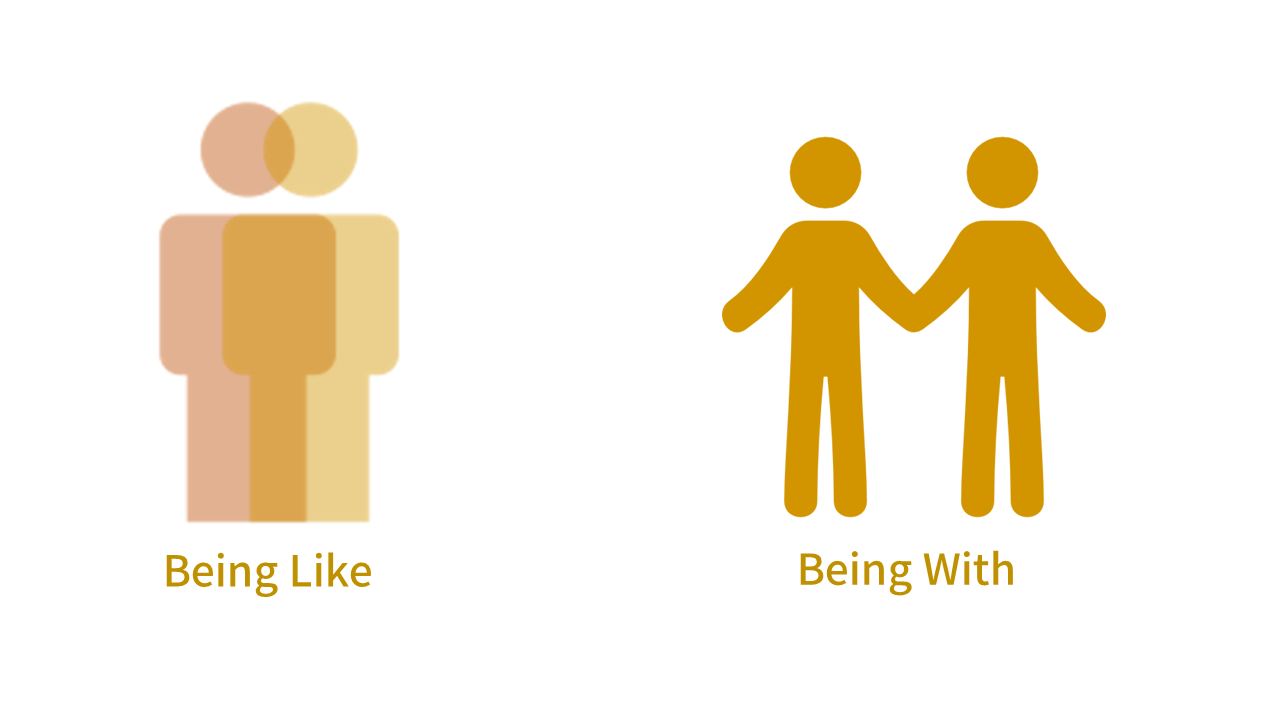

Empathy-building premised on being like someone to understand their experiences may displace firsthand perspectives. Being with one another may be a first step toward fostering reciprocal partnerships.

Empathy-building premised on being like someone to understand their experiences may displace firsthand perspectives. Being with one another may be a first step toward fostering reciprocal partnerships.While altruistic, we show how empathy-building may actually distance people with disabilities from the design work we are trying to bring them closer to. For example, designers who use disability simulation techniques such as blindfolds to empathize with blind users may not need to consider the user with disabilities; instead, they may focus on their own experience wearing a blindfold. To make this argument, we examined publicly available accounts of empathy-building and popularized design thinking toolkits to describe how designers (as the empathizers) position their work to address the experiences of people with disabilities (as the empathized). Such separation can position people with disabilities as inspirations, in turn subverting their firsthand perspectives and important contributions.

In response, we argue for letting go of empathy as an achievement— something to build, model, or reach within design. Instead, we draw from decades of disability scholarship and activism to recover empathy as a creative process of reciprocation. Specifically, we suggest strategies for maintaining ongoing partnerships premised on listening and sharing firsthand experiences.

Interdependence as a Frame for Assistive Technology Design and Research

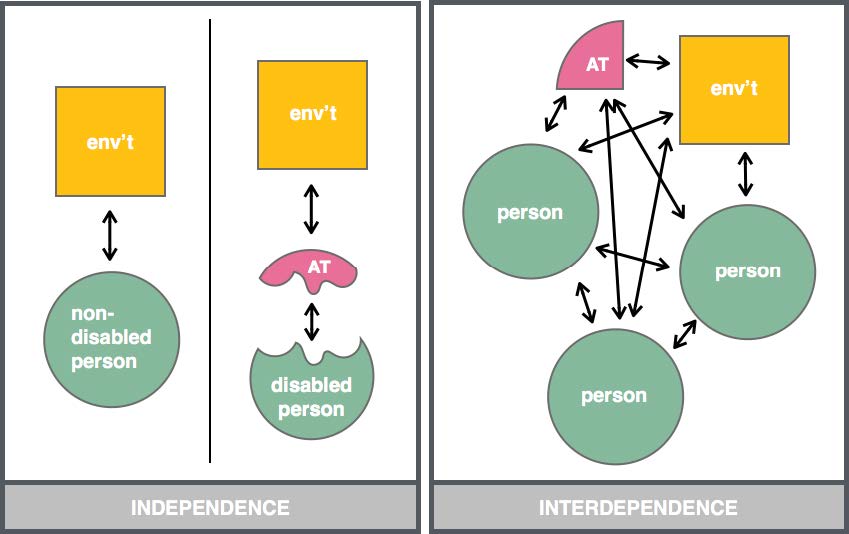

Independence is a very important word for people with disabilities. The Disability Rights Movement in the United States premised on people with disabilities asserting their equal rights and taking charge of defining and securing their own accommodations. As such, assistive technology design and research has adopted this important goal, leveraging computing power to enable people with disabilities to live more independently. During this collaboration, colleagues Stacy Branham, Erin Brady, and I responded to a somewhat different trend we were noticing in our research with people with disabilities. We were intrigued how often our participants worked together to make objects, spaces, and experiences more accessible for and with others with disabilities. Drawing on Disability Studies scholarship and Disability Justice activism, we decided to call this phenomena interdependence to honor and build upon the important disabled people who have written about the term outside the assistive technology field.

An independence frame (left) emphasizes an individual’s relationship with the environment. Assistive technology (AT) devices are meant to bridge a perceived gap between disabled bodies and environments designed for non-disabled people. An interdependence frame (right) emphasizes the relationships among people, ATs, and environments.

An independence frame (left) emphasizes an individual’s relationship with the environment. Assistive technology (AT) devices are meant to bridge a perceived gap between disabled bodies and environments designed for non-disabled people. An interdependence frame (right) emphasizes the relationships among people, ATs, and environments.We then came up with four tenets that outline what interdependence can offer if taken up as a frame for assistive technology, and we hope any, design and research. First, interdependence focuses on relationships as a foundation where access is built or not built and assumes all parties in an interaction are contributing to and shaped by that interaction in some way. Second, interdependence makes available the possibility that multiple humans, objects, and environments can come together simultaneously toward these ends. Third, since interdependence assumes all parties interacting are contributing, it makes more visible the often underrecognized work done by people with disabilities. Finally, in recognizing this important work, interdependence challenges predominant hierarchies that prefer ability. Read our Best Student Paper Awarded ASSETS 2018 work for examples from all of our research that contextualize these tenets. Finally, we present interdependence to complement, not replace, independence as we recognize many people with disabilities are still fighting for basic rights to make choices about their own lives.

How Teens Take, Edit, and Share Photos on Social Media

As a blind photography enthusiast, I was incredibly excited to explore how visually impaired teens interact with emergent social media like Instagram and Snapchat during an internship at Microsoft Research with Ed Cutrell and Merrie Morris. Most accessibility-related social media research focuses on totally blind, older people. Visually impaired people have unique accessibility needs and they want to use the vision they do have to engage with photos. Since teens are super users of newer social media like Instagram and Snapchat, we interviewed 16 to 19-year olds with visual impairments to learn their browsing and posting behaviors and challenges. We found that visually impaired teens engage with these social media like their sighted peers by editing photos according to trends. But they also edited photos to make them more visible raising questions about expanding research on color visibility and vision impairment, since most focuses on text and background optimization as opposed to optimizing the complex color pallets found in photos.

A view of some of the vision oriented accessibility settings on a smartphone.

A view of some of the vision oriented accessibility settings on a smartphone.Additionally, reading ephemeral content was difficult for our participants, and they grappled with social implications that screenshotting snaps was an invasion of privacy as screenshotting gave them additional viewing time they needed to understand snaps.

Our research confirms that visually impaired people are attempting to engage with social media as much as they can, but they still encounter frustrating barriers. We hope researchers and designers of social media prioritize increasing accessibility for this demographic which wants to engage with these social media more. The linked paper provides more insights into their photography and social media use and offers design recommendations to increase their accessibility.

Using a Design Workshop to Explore Accessible Ideation

Some Human-Centered Design activities, like brainstorming, may not be accessible as they are popularly taught. For example, many people learn to brainstorm by hand-drawing ideas in a short amount of time. This might not be feasible for people with vision and motor impairments.

We conducted a workshop with 40 engineering professionals, including 7 with disabilities. They first ideated in teams on a design challenge. Second, they reflected on access barriers. Finally, they ideated and rapidly prototyped potential solutions to alleviate the access barriers.

We conducted a workshop with 40 engineering professionals, including 7 with disabilities. They first ideated in teams on a design challenge. Second, they reflected on access barriers. Finally, they ideated and rapidly prototyped potential solutions to alleviate the access barriers.In summary, offering a multitude of ideation materials can better include people with vision and motor impairments (tactile and 3d materials, computer-based brainstorming for example) taking turns sharing ideas can help ensure people with hearing impairments, those who are less outgoing, and remote participants have a say, and organizing ideas can help people with visual and cognitive impairments better follow along. One team found that dividing tasks according to strengths helped involve everyone, recommending people take learning style or strengths assessments before diving into design challenges.

The linked poster abstract offers more details about this project and demonstrates that a workshop can be a fruitful method for quickly trying potential accessible solutions. In conclusion, if ideation is done more flexibly, it could allow all team members to brainstorm with methods that suit their strengths and abilities.

Prostheses and Making

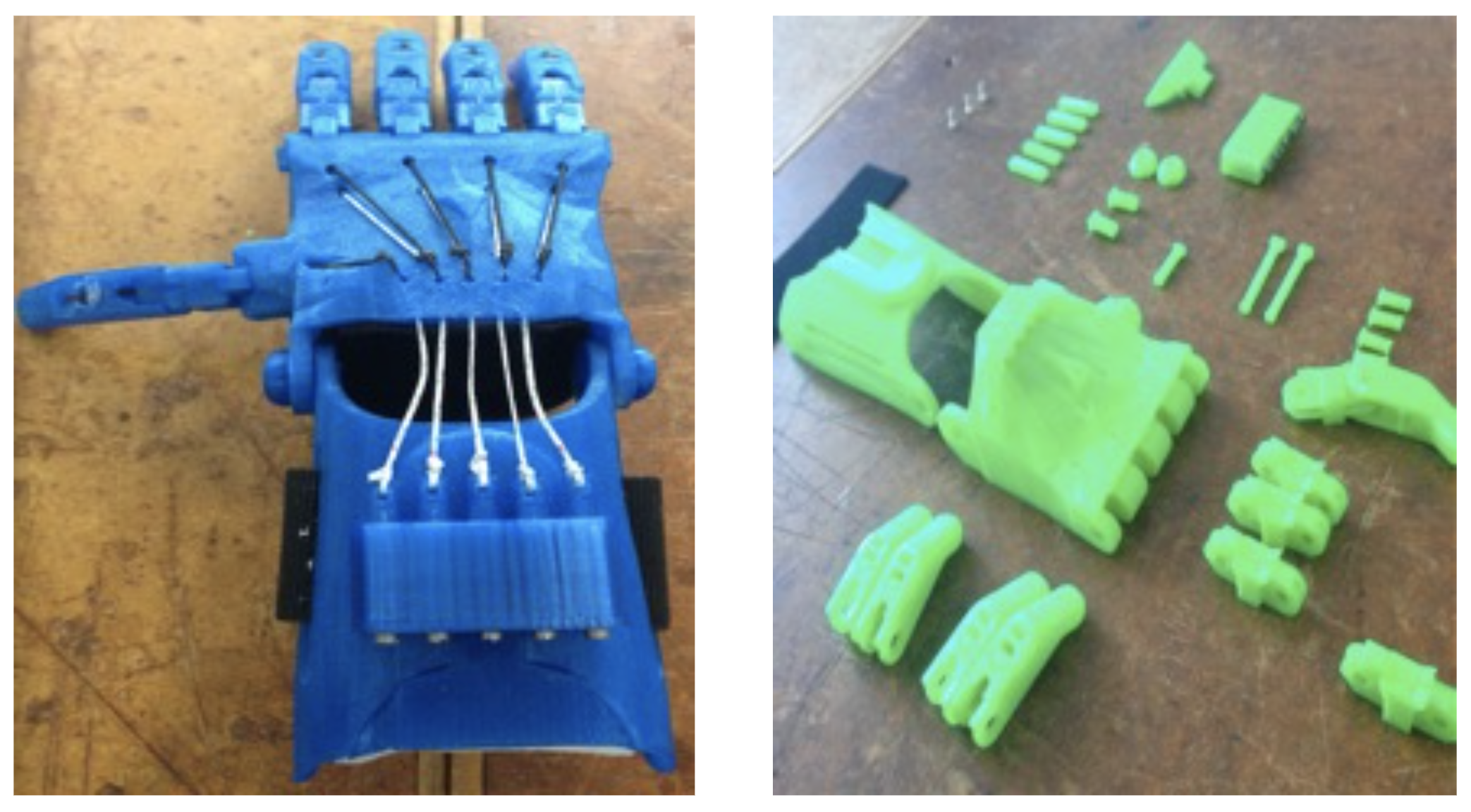

As making meets assistive technology, we were interested in how people with upper limb loss incorporate that experience and prostheses into their identities and negotiations of social norms. One example of the two communities meeting is e-NABLE, which coalesces volunteers to partner with a user to redesign open-source hand designs on Thingiverse to fit the user’s needs, and 3D-prints the hands for no cost.

Left: Photo of an e-NABLE hand

Right: Photo of pieces of an e-NABLE hand, disassembled.

We interviewed 14 people with upper limb loss. Some used prostheses prescribed by a prosthetist. Some used e-NABLE hands, and others did not use prostheses. We learned that similar to other objects, participants incorporate prostheses, other objects appropriated as assistive technologies, and limb loss into their identities. Participants also negotiated normalcy, fluctuating between striving to appear as someone with two arms and other times, explicitly drawing attention to limb loss or prostheses. From our participants, we highlight the potential for communities like e-NABLE to make prostheses low cost and customizable. Yet, with that comes a need to step back and consider potential pitfalls such as the fact that none of the participants who had tried one use their e-NABLE hands, and design and assembly for our participants was not accessible. The HCI community should consider what agency users have as making and assistive technology further entwine, and prioritize thought and action to account for the intimate, personal relationships people develop with assistive objects.

This project was advised by Daniela Rosner and Kat Steele, and I collaborated with Keting Cen. Watch our CHI video preview and download our 2016 paper.